This is a story from my thesis project, an oral history of

the Tiananmen Square Massacre in Beijing, 1989.

Press play to begin:

We didn’t think they were gunshots at first. We thought someone was setting off firecrackers—we couldn’t believe it was actually gunfire. But it didn’t sound like firecrackers, and it kept going and going, so after a while we all went outside, the neighbors and I. Only then did we realize that they were real gunshots.

Scroll down to continue

I was working at a university in Beijing at the time, so I was pretty much there for the whole thing, start to finish. I wasn’t directly involved, though. I think it all started in April, when General Secretary Hu Yaobang died. When he died everyone was talking about corruption, how concerned they were about it and how the government and Communist Party should do something to address it.

We all supported the students, even us teachers. We thought they were making reasonable demands. The students weren’t the only ones who had these sorts of demands, they were just the ones who went into the streets about it, that’s it. We all went to Tiananmen Square. We went ourselves. We wanted the people in power to recognize us, the normal people, just to hear what we were asking for. So a lot of people went to the square, not just students. It was workers and neighbors and citizens, ordinary citizens—everyone went, at least in the beginning.

General Secretary Hu Yaobang was purged in 1987 due to accusations of "bourgeois liberalism" and died on April 15, 1989. Public mourning for Hu became an implicit criticism of the current Party leadership, as well as an opportunity for mass gatherings—after his memorial service in Tiananmen on the 22nd, the square continued to be occupied until June 4th.

Things were like this at the start. All of us supported the students and didn’t think they were doing anything wrong or objectionable. So when the People’s Daily came out with that editorial, it was like they delivered their verdict—all of a sudden they characterized the movement as terrible and anti-government.

We Must Unequivocally Stand Against Turmoil

People's Daily

Published on April 26th in the official Party newspaper, the editorial characterized the movement as “a planned conspiracy” that aimed to “fundamentally negate the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the socialist system.” Tens of thousands of people flooded the Square the next day in the largest demonstrations to date, calling for the editorial be rescinded.

We didn’t think that was right at all. We were like, how could you say this about the students? How could you interpret the situation this way? But at the same time—how do I say this? As things progressed our views started to diverge from the students’. At the start, everyone thought that this sort of thing, letting the Party hear the demands of the people—that was all good, and the protests were orderly, nothing too extreme or excessive. But afterwards, especially when those three students knelt at the Great Hall of the People to submit their petition, we started to get a bit anxious, because we thought the students were just too young.

During Hu Yaobang's memorial service, three students knelt at the steps of the Great Hall of the People—the site of China's legislature—and demanded that Premier Li Peng come out and personally accept their handwritten petition. In imperial times, subjects would kneel before government buildings to submit their grievances, and benevolent officials were expected to hear their subjects' concerns. The students knelt for half an hour; Li Peng stayed inside.

Seven-Point Petition

-

Reevaluate and praise Hu Yaobang's contributions

-

Negate the previous anti-"spiritual pollution" and anti-"Bourgeois Liberation" movements

-

Allow unofficial press and freedom of speech

-

Publish government leaders' income and holdings

-

Abolish the "Beijing Ten-Points" [restricting public assembly and demonstrations]

-

Increase education funding and enhance the compensation for intellectuals

-

Report this movement faithfully

Can you imagine someone going outside and saying, “Let me hear your petition, we’ll figure something out”? The government would never do that. No way. It was too naive. It couldn’t be like what the students were hoping for, where you accomplish everything in one or two days or even one or two months. Those students really were too young. We supported the students, we had solidarity, the Chinese people should be able to voice their concerns, but that way of doing things was hopeless.

At our school there were a lot of instructors who tried to hold the students back, but they wouldn’t listen. They’d say you were backwards, you weren’t any good. It was like during the Up to the Mountains, Down to the Countryside movement, when we went out to the villages. Now that was revolution. We were 17, 18, 19 years old and filled with self-righteousness—we understood the students all too well.

Going down to the countryside for those couple years had its advantages, though. It toughened us; we ate a lot of bitterness. We got to learn how people at the very bottom of Chinese society actually lived. We were all from the big cities, so living at the bottom made us better understand what conditions in China were really like. So there were some benefits. Of course, I’m one of the lucky ones. I spent time in the villages, but I was still able to attend university. It was a shame—a lot of people missed their opportunity to go to university and never had another chance. So when I look back at how passionate we were, I think that’s just how young people are. It was the same with the students of June 4th. Our faith was unshakable.

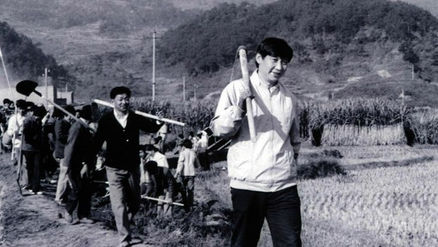

Starting in 1968, two years after the Cultural Revolution began, millions of urban youths voluntarily and involuntarily relocated to rural areas during the Up to the Mountains, Down to the Countryside Movement, including current president Xi Jinping (bottom center). Many lost their chance to attend university; some never returned home. They are considered China’s “Lost Generation.”

The soldiers were victims, too. They’d no idea what was going on. They came in to suppress the protests—they were just these baby-faced kids, maybe 17 or 18 or 19. They were clueless, just dropped into Beijing and told something about a counter-revolutionary riot they had to suppress. They didn’t know anything. It was pathetic. They shot ‘cause they were ordered to shoot.

There was an army unit stationed near the place I was living at. They must’ve come into the city from Hebei Province or somewhere, on foot, running for hours in the middle of the night. You took one look at them and you saw that they were all young. We were like, “Why are you in Beijing? Do you know what’s going on here?” And they were like, “We don’t know either! We were told something about a disturbance or a counter-revolutionary riot or something.” They had no understanding. No idea.

About 150,000 martial law troops entered Beijing in the early hours of May 20th. Residents constructed makeshift barricades—street dividers, park benches, commandeered buses—and surrounded the soldiers’ trucks and personnel carriers, delivering political lectures and offering food and drink. Many soldiers from this initial wave expressed sympathy for the protesters.

This whole thing, every single person, they were all young. They were all human beings. So when things reached that final point—it was a tragedy, it made your heart break. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying I blame the students for stirring things up. Their demands weren’t wrong. We all supported them.

I don’t really understand politics. I don’t know what the best solution to this sort of problem is. I don’t know either, and I don’t think talking about it now is useful. Because in those conditions—which path do you take? How do you best contain how things escalated? How do you prevent the massacre? No one thought they’d actually open fire. We didn’t even consider it. Everyone was shocked. So you can’t talk about “maybe.” History doesn’t have “maybes.” What happened, happened.

How do I say this? I guess, it was the reason, or at least part of the reason, that I came to America next semester. My husband was already in the US and I was at home, taking care of our one-year-old. I didn’t want to go. The plan was for him to come back after he finished his degree. But after what happened, after June 4th, I thought, alright. Let’s go.

They were just too young.